This blog entry/page is my online/on demand presentation for the 2022 Computers and Writing Conference at East Carolina University.

I’m disappointed that I’m not at this year’s Computers and Writing Conference in person. I haven’t been to C&W since 2018 and of course there was no conference in 2020 or 2021. So after the CCCCs prematurely pulled the plug on the face to face conference a few months ago, I was looking forward to the road trip to Greenville. Alas, my own schedule conflicts and life means that I’ll have to participate in the online/on-demand format this time around. I don’t know if that means anyone (other than me) will actually read this, so as much as anything else, this presentation/blog post– which is too long, full of not completely substantiated/documented claims, speculative, fuzzy, and so forth– is a bit of note taking and freewriting meant mostly for myself as I think about how to present this research in future articles, maybe even a book. If a few conference goers and my own blog readers find this interesting, all the better.

I’m disappointed that I’m not at this year’s Computers and Writing Conference in person. I haven’t been to C&W since 2018 and of course there was no conference in 2020 or 2021. So after the CCCCs prematurely pulled the plug on the face to face conference a few months ago, I was looking forward to the road trip to Greenville. Alas, my own schedule conflicts and life means that I’ll have to participate in the online/on-demand format this time around. I don’t know if that means anyone (other than me) will actually read this, so as much as anything else, this presentation/blog post– which is too long, full of not completely substantiated/documented claims, speculative, fuzzy, and so forth– is a bit of note taking and freewriting meant mostly for myself as I think about how to present this research in future articles, maybe even a book. If a few conference goers and my own blog readers find this interesting, all the better.

Because of the nature of these on-demand/online presentations generally and also because of the perhaps too long/freewriting feel of what I’m getting at here, let me start with a few “to long, didn’t read” bullet points. I’m not even going to write anything else here to explain this, but it might help you decide if it’s worth continuing to read. (Hopefully it is…)

Because of the nature of these on-demand/online presentations generally and also because of the perhaps too long/freewriting feel of what I’m getting at here, let me start with a few “to long, didn’t read” bullet points. I’m not even going to write anything else here to explain this, but it might help you decide if it’s worth continuing to read. (Hopefully it is…)

The research I’m continuing is a project I have been calling “Online Teaching and ‘The New Normal,’” which I started in early fall 2020. Back then, I wrote a brief article and was an invited speaker at an online conference held by a group in Belgium– this after someone there saw a post I had written about Zoom on my blog, which is one of the reasons why I keep blogging after all these years. I gave a presentation (that got shuffled away into the “on demand” format) at the most recent CCCCs where I introduced some of my broad assumptions about teaching online, especially about the affordances of asynchronously versus synchronously, and where I offered a few highlights of the survey results. I also wrote an article-slash-website for Computers and Composition Online which goes into much more detail about the results of the survey. That piece is in progress, though it will be available soon. If you have the time and/or interest, I’d encourage you to check out the links to those pieces as well.

The research I’m continuing is a project I have been calling “Online Teaching and ‘The New Normal,’” which I started in early fall 2020. Back then, I wrote a brief article and was an invited speaker at an online conference held by a group in Belgium– this after someone there saw a post I had written about Zoom on my blog, which is one of the reasons why I keep blogging after all these years. I gave a presentation (that got shuffled away into the “on demand” format) at the most recent CCCCs where I introduced some of my broad assumptions about teaching online, especially about the affordances of asynchronously versus synchronously, and where I offered a few highlights of the survey results. I also wrote an article-slash-website for Computers and Composition Online which goes into much more detail about the results of the survey. That piece is in progress, though it will be available soon. If you have the time and/or interest, I’d encourage you to check out the links to those pieces as well.

I started this project in early fall 2020 for two reasons. First, there was the “natural experiment” created by Covid. Numerous studies have claimed online courses can be just as effective as face to face courses, but one of the main criticisms of these studies is the problem of self selection: that is, because students and teachers engage in the format voluntarily, it’s not possible to have subjects randomly assigned to either a face to face course or an online course, and that kind of randomized study is the gold standard in the social sciences. The natural experiment of Covid enabled a version of that study because millions of college students and instructors had no choice but to take and teach their classes online.

I started this project in early fall 2020 for two reasons. First, there was the “natural experiment” created by Covid. Numerous studies have claimed online courses can be just as effective as face to face courses, but one of the main criticisms of these studies is the problem of self selection: that is, because students and teachers engage in the format voluntarily, it’s not possible to have subjects randomly assigned to either a face to face course or an online course, and that kind of randomized study is the gold standard in the social sciences. The natural experiment of Covid enabled a version of that study because millions of college students and instructors had no choice but to take and teach their classes online.

Second, I was surprised by the large number of my colleagues around the country who said on social media and other platforms that they were going to teach their online classes synchronously via a platform like Zoom rather than asynchronously. I thought this choice– made by at least 60% of college faculty across the board during the 2020-21 school year– was weird.

Based both on my own experiences teaching some of my classes online since 2005 and the modest amount of research comparing synchronous and asynchronous modes for online courses, I think that asynchronous online courses are probably more effective than synchronous online courses. But that’s kind of beside the point, actually. The main reason why at least 90% of online courses prior to Covid were taught asynchronously is scheduling and the imperative of providing access. Prior to Covid, the primary audience for online courses and programs were non-traditional students. Ever since the days of correspondence courses, the goal of distance ed has been to help “distanced” students– that is, people who live far away from the brick and mortar campus– but also people who are past the traditional undergraduate age, who have “adult” obligations like mortgages and dependents and careers, and people who are returning to college either to finish the degree they started some years before, or to retool and retrain after having finished a degree earlier. Asynchronous online courses are much easier to fit into busy and changing life-slash-work schedules than synchronous courses– either online ones of f2f. Sure, traditional and on-campus students often take asynchronous courses for similar scheduling reasons, but again and prior to Covid, non-traditional students were the primary audience for online courses. In fact, most institutions that primarily serve traditional students– that is, 18-22 year olds right out of high school who live on or near campus and who attend college full-time (and perhaps work part-time to pay some of the bills)– did not offer many online courses, nor was there much of a demand for online courses from students at these institutions. I’ll come back to this point later.

Based both on my own experiences teaching some of my classes online since 2005 and the modest amount of research comparing synchronous and asynchronous modes for online courses, I think that asynchronous online courses are probably more effective than synchronous online courses. But that’s kind of beside the point, actually. The main reason why at least 90% of online courses prior to Covid were taught asynchronously is scheduling and the imperative of providing access. Prior to Covid, the primary audience for online courses and programs were non-traditional students. Ever since the days of correspondence courses, the goal of distance ed has been to help “distanced” students– that is, people who live far away from the brick and mortar campus– but also people who are past the traditional undergraduate age, who have “adult” obligations like mortgages and dependents and careers, and people who are returning to college either to finish the degree they started some years before, or to retool and retrain after having finished a degree earlier. Asynchronous online courses are much easier to fit into busy and changing life-slash-work schedules than synchronous courses– either online ones of f2f. Sure, traditional and on-campus students often take asynchronous courses for similar scheduling reasons, but again and prior to Covid, non-traditional students were the primary audience for online courses. In fact, most institutions that primarily serve traditional students– that is, 18-22 year olds right out of high school who live on or near campus and who attend college full-time (and perhaps work part-time to pay some of the bills)– did not offer many online courses, nor was there much of a demand for online courses from students at these institutions. I’ll come back to this point later.

I conducted my IRB approved survey from December 2020 to June 2021. The survey was limited to college level instructors in the U.S. who taught at least one class completely online (that is, not in some hybrid format that included f2f instruction) during the 2020-21 school year. Using a very crude snowball sampling method, I distributed the survey via social media and urged participants to share the survey with others. I had 104 participants complete this survey, and while I was hoping to recruit participants from a wide variety of disciplines, most were from a discipline related to English studies. This survey was also my tool for recruiting interview subjects: the last question of the survey asked if participants would be interested in a follow-up interview, and 75 indicated that they would be.

I conducted my IRB approved survey from December 2020 to June 2021. The survey was limited to college level instructors in the U.S. who taught at least one class completely online (that is, not in some hybrid format that included f2f instruction) during the 2020-21 school year. Using a very crude snowball sampling method, I distributed the survey via social media and urged participants to share the survey with others. I had 104 participants complete this survey, and while I was hoping to recruit participants from a wide variety of disciplines, most were from a discipline related to English studies. This survey was also my tool for recruiting interview subjects: the last question of the survey asked if participants would be interested in a follow-up interview, and 75 indicated that they would be.

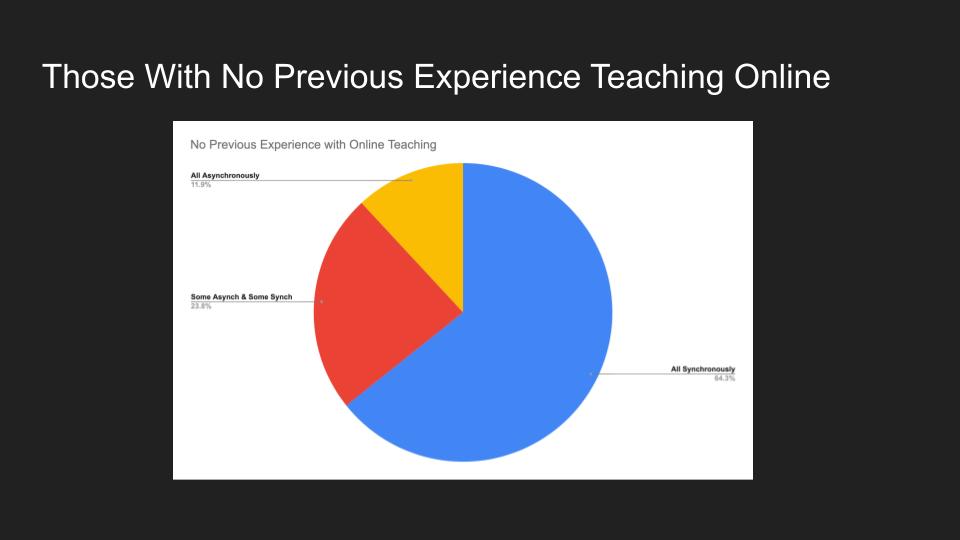

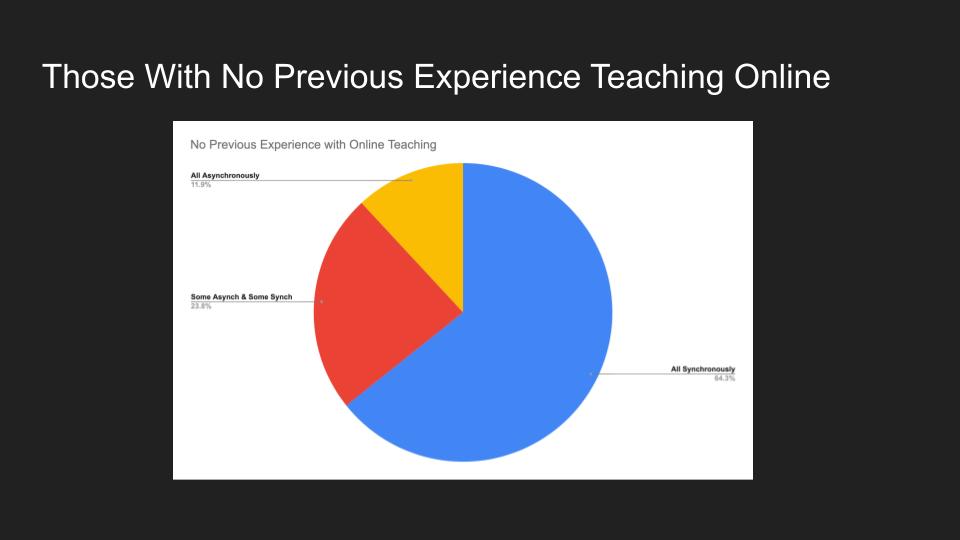

One of the findings from the survey that I discussed in my CCCCs talk was that those survey participants who had no previous experience teaching online were over three times more likely to have elected to teach their online classes synchronously during Covid than those who had had previous teaching experience. As this pie chart shows, almost two-thirds of faculty with no prior experience teaching online elected to teach synchronously and only about 12% of survey participants who had no previous experience teaching online elected to teach asynchronously.

One of the findings from the survey that I discussed in my CCCCs talk was that those survey participants who had no previous experience teaching online were over three times more likely to have elected to teach their online classes synchronously during Covid than those who had had previous teaching experience. As this pie chart shows, almost two-thirds of faculty with no prior experience teaching online elected to teach synchronously and only about 12% of survey participants who had no previous experience teaching online elected to teach asynchronously.

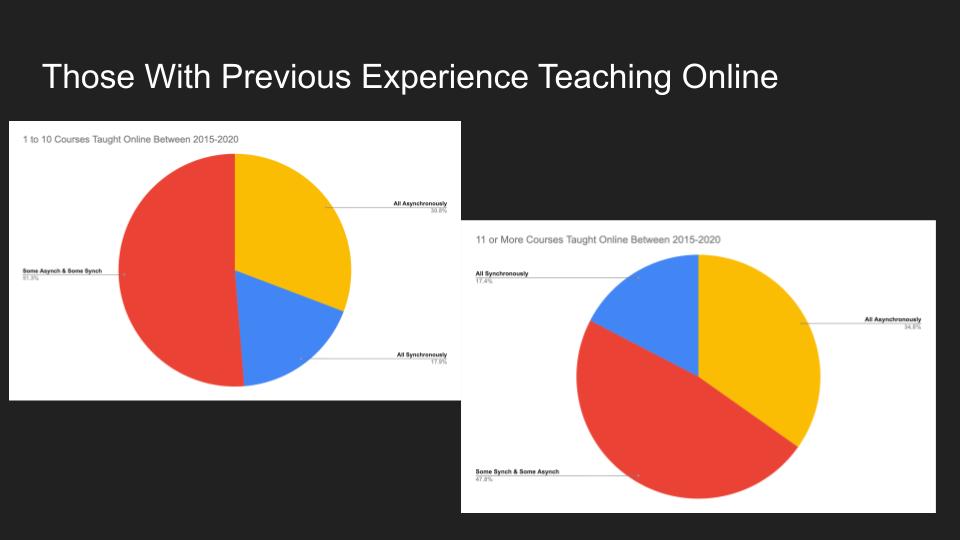

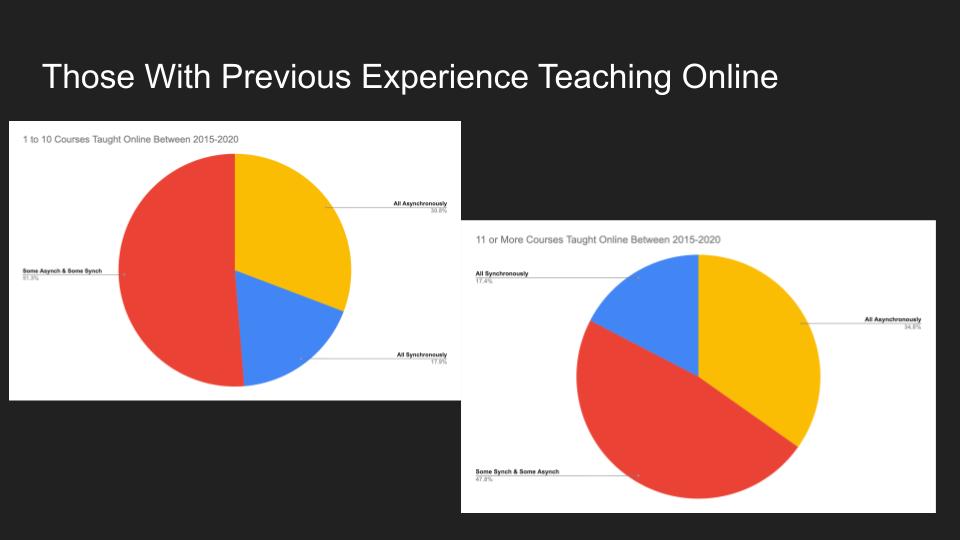

In contrast, about a third of faculty who had had previous online experience elected to teach online asynchronously and less than 18% decided to teach online synchronously. Interestingly, the amount of previous experience with teaching online didn’t seem to make much difference– that is, those who said that prior to covid they had taught over 20 sections online were about as likely to have taught asynchronously or to use both synchronous and asynchronous approaches as those who had only taught 1 to 5 sections online prior to the 2020-21 school year.

In contrast, about a third of faculty who had had previous online experience elected to teach online asynchronously and less than 18% decided to teach online synchronously. Interestingly, the amount of previous experience with teaching online didn’t seem to make much difference– that is, those who said that prior to covid they had taught over 20 sections online were about as likely to have taught asynchronously or to use both synchronous and asynchronous approaches as those who had only taught 1 to 5 sections online prior to the 2020-21 school year.

For the forthcoming Computers and Composition Online article, I go into more detail about the results of the survey along with incorporating some of the initial impressions and feedback I’ve received from the surveys to date.

But for the rest of this presentation, I’ll focus on the interviews I have been conducting. I started interviewing participants in January 2022, and these interviews are still in progress. Since this is the kind of conference where people do often care about the technical details: I’m using Zoom to record the interviews and then a software called Otter.ai to create a transcription. Otter.ai isn’t free– in fact, at $13 for the month to month and unlimited usage plan, it isn’t especially cheap– and there are of course other options for doing this. But this is the best and easiest approach I’ve found so far. Most of the interviews I’ve conducted so far run between 45 and 90 minutes, and what’s amazing is Otter.ai can change the Zoom audio file into a transcript that’s about 85% correct in less than 15 minutes. Again, nerdy and technical details, but for changing audio recordings into mostly correct transcripts, I cannot say enough good things about it.

But for the rest of this presentation, I’ll focus on the interviews I have been conducting. I started interviewing participants in January 2022, and these interviews are still in progress. Since this is the kind of conference where people do often care about the technical details: I’m using Zoom to record the interviews and then a software called Otter.ai to create a transcription. Otter.ai isn’t free– in fact, at $13 for the month to month and unlimited usage plan, it isn’t especially cheap– and there are of course other options for doing this. But this is the best and easiest approach I’ve found so far. Most of the interviews I’ve conducted so far run between 45 and 90 minutes, and what’s amazing is Otter.ai can change the Zoom audio file into a transcript that’s about 85% correct in less than 15 minutes. Again, nerdy and technical details, but for changing audio recordings into mostly correct transcripts, I cannot say enough good things about it.

To date, I’ve conducted 24 interviews, and I am guessing that I will be able to conduct between 15 and 30 more, depending on how many of the folks who originally volunteered to be interviewed are still willing.

This means I already have about 240,000 words of transcripts, and I have to say I am at something of a loss as to what to “do” with all of this text in terms of coding, analysis, and the like. The sorts of advice and processes offered by books like Geisler’s and Swarts’ Coding Streams of Language and Saldaña’s The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers seems more fitting for analyzing sets of texts in different genres– say an archive for an organization that consists of a mix of memos, emails, newsletters, academic essays, reports, etc.– or of a collection of ethnographic observations. So for me, it doesn’t so much feel like I am collecting a lot of qualitative data meant to be coded and analyzed based on particular word choices or sentence structures or what-have-you, and more like good old-fashioned journalism. If I had been at this conference in person or if there was a more interactive component to this online presentation, this is something I would have wanted to talk more about with the kind of scholars and colleagues involved with computers and writing because I can certainly use some thoughts on how to handle my growing collection of interviews. In any event, my current focus– probably through the end of this summer– is to keep collecting the interviews from willing participants and to figure out what to do with all of this transcript data later. Perhaps that’s what I can talk about at the computers and writing conference at UC Davis next year.

This means I already have about 240,000 words of transcripts, and I have to say I am at something of a loss as to what to “do” with all of this text in terms of coding, analysis, and the like. The sorts of advice and processes offered by books like Geisler’s and Swarts’ Coding Streams of Language and Saldaña’s The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers seems more fitting for analyzing sets of texts in different genres– say an archive for an organization that consists of a mix of memos, emails, newsletters, academic essays, reports, etc.– or of a collection of ethnographic observations. So for me, it doesn’t so much feel like I am collecting a lot of qualitative data meant to be coded and analyzed based on particular word choices or sentence structures or what-have-you, and more like good old-fashioned journalism. If I had been at this conference in person or if there was a more interactive component to this online presentation, this is something I would have wanted to talk more about with the kind of scholars and colleagues involved with computers and writing because I can certainly use some thoughts on how to handle my growing collection of interviews. In any event, my current focus– probably through the end of this summer– is to keep collecting the interviews from willing participants and to figure out what to do with all of this transcript data later. Perhaps that’s what I can talk about at the computers and writing conference at UC Davis next year.

But just to give a glimpse of what I’ve found so far, I thought I’d focus on answers to two of the dozen or so questions I have been sure to ask each interviewee:

But just to give a glimpse of what I’ve found so far, I thought I’d focus on answers to two of the dozen or so questions I have been sure to ask each interviewee:

- Why did you decide to teach synchronously (or asynchronously)?

- Knowing what you know now and after your experience teaching online during the 2020-21 school year, would you teach online again– voluntarily– and would you prefer to do it synchronously or asynchronously?

In my survey, participants had to answer a close-ended question to indicate if they were teaching online synchronously, asynchronously, or some classes synchronously and some asynchronously. There was no “other” option for supplying a different answer. This essentially divided survey participants into two groups because I counted those who were teaching in both formats as synchronous for the other questions on the survey. Also, I excluded from the survey faculty who were teaching with a mix of online and face to face modes because I wanted to keep this as simple as possible. But early on, the interviews made it clear that the mix of modes at most universities was far more complex. One interviewee said that prior to Covid, the choices faculty had for teaching (and the choices students saw in the catalog) was simply online or on campus. Beginning in Fall 2020 though, faculty could choose “fully online asynchronous, fully online synchronous, high flex synchronous, so (the instructor) is stand in the classroom and everyone else is in WebEx of Teams, and fully in the classroom and no option… you need to be in the classroom.”

In my survey, participants had to answer a close-ended question to indicate if they were teaching online synchronously, asynchronously, or some classes synchronously and some asynchronously. There was no “other” option for supplying a different answer. This essentially divided survey participants into two groups because I counted those who were teaching in both formats as synchronous for the other questions on the survey. Also, I excluded from the survey faculty who were teaching with a mix of online and face to face modes because I wanted to keep this as simple as possible. But early on, the interviews made it clear that the mix of modes at most universities was far more complex. One interviewee said that prior to Covid, the choices faculty had for teaching (and the choices students saw in the catalog) was simply online or on campus. Beginning in Fall 2020 though, faculty could choose “fully online asynchronous, fully online synchronous, high flex synchronous, so (the instructor) is stand in the classroom and everyone else is in WebEx of Teams, and fully in the classroom and no option… you need to be in the classroom.”

I was also surprised at the extent to which most of my interviewees reported that their institution provided faculty a great deal of autonomy in selecting the teaching mode that worked best for their circumstances. So far, I have only interviewed two or three people who said they had no choice but to teach in the mode assigned by the institution. A number of folks said that their institution strongly encouraged faculty to teach synchronously to replicate the f2f experience, but even under those circumstances, it seems most faculty had a fair amount of flexibility to teach in a mode that best fits into the rest of their life. As one person, a non-tenure-track but full time instructor said, “basically, the university said ‘we don’t care that much, especially if you’re… a parent and your kids aren’t going to school and you have to physically be home.’” This person’s impression was that while most of their colleagues were teaching synchronous courses with Zoom, there were “a lot of individual class sessions that were moved asynchronous, and maybe even a few classes that essentially went asynchronous.”

A number of interviewees mentioned that this level of flexibility offered to faculty from their institutions was unusual; one interviewee described the flexibility offered to faculty about their preferred teaching mode a “rare win” against the administration. After all, during the summer of 2020 and when a lot of the plans for going forward with the next school year were up in the air, there were a lot of rumors at my institution (and, judging from Facebook, other institutions as well) that individual faculty who wanted to continue to teach online in Fall of 2020 because of the risks of Covid were were going to have go through a process involving the Americans with Disabilities Act. So the fact that just about everyone I talked to was allowed to teach online and in the mode that they preferred was both surprising and refreshing.

As to why faculty elected to teach in one mode or the other: I think there were basically three reasons. First, as that quote I had above just mentioned, many faculty said concerns about how Covid was impacting their own home lives shaped the decision for either for teaching synchronously or asynchronously. Though again, most of my survey and interview subjects who hadn’t taught online before taught synchronously, and, not surprisingly, some of those interviewees told stories about how their pets, children, and other family members would become regular visitors in the class Zoom sessions. In any event, the risks and dangers of Covid– especially in Fall 2020 and early in 2021 when the data on the risks of transmission in f2f classrooms was unclear and before there was a vaccine– was of course the reason why so many of us were forced into online classes during the pandemic. And while it did indeed create a natural experiment for testing the effectiveness of online courses, I wonder if Covid ended up being such an enormous factor in all of our lives that it essentially skewed or trumped the experiences of teaching online. After all, it is kind of hard for teachers and students alike to reflect too carefully on the advantages and disadvantages of online learning when the issue dominating their lives was a virus that was sickening and killing millions of people and disrupting pretty much every aspect of modern society as we know it.

As to why faculty elected to teach in one mode or the other: I think there were basically three reasons. First, as that quote I had above just mentioned, many faculty said concerns about how Covid was impacting their own home lives shaped the decision for either for teaching synchronously or asynchronously. Though again, most of my survey and interview subjects who hadn’t taught online before taught synchronously, and, not surprisingly, some of those interviewees told stories about how their pets, children, and other family members would become regular visitors in the class Zoom sessions. In any event, the risks and dangers of Covid– especially in Fall 2020 and early in 2021 when the data on the risks of transmission in f2f classrooms was unclear and before there was a vaccine– was of course the reason why so many of us were forced into online classes during the pandemic. And while it did indeed create a natural experiment for testing the effectiveness of online courses, I wonder if Covid ended up being such an enormous factor in all of our lives that it essentially skewed or trumped the experiences of teaching online. After all, it is kind of hard for teachers and students alike to reflect too carefully on the advantages and disadvantages of online learning when the issue dominating their lives was a virus that was sickening and killing millions of people and disrupting pretty much every aspect of modern society as we know it.

Second — and perhaps this is just obvious– people did what they already knew how to do, or they did what they thought would be the path of least resistance. Most faculty who decided to teach asynchronously had previous experience teaching asynchronously– or they were already teaching online asynchronously. As one interviewee put it, “Spring 2020, I taught all three classes online. And then COVID showed up, and I was already set up for that because, I was like ‘okay, I’m already teaching online,’ and I’m already teaching asynchronously, so…” That was the situation I was in when we first went into Covid lockdown in March 2020– though in my experience, that didn’t mean that Covid was a non-factor in those already online classes.

Second — and perhaps this is just obvious– people did what they already knew how to do, or they did what they thought would be the path of least resistance. Most faculty who decided to teach asynchronously had previous experience teaching asynchronously– or they were already teaching online asynchronously. As one interviewee put it, “Spring 2020, I taught all three classes online. And then COVID showed up, and I was already set up for that because, I was like ‘okay, I’m already teaching online,’ and I’m already teaching asynchronously, so…” That was the situation I was in when we first went into Covid lockdown in March 2020– though in my experience, that didn’t mean that Covid was a non-factor in those already online classes.

Most faculty who decided to teach synchronously– particularly those who had not taught online before– thought teaching synchronously via Zoom would require the least amount of work to adjust from the face to face format, though few interviewees said anything so direct. I spoke with one Communications professor who, just prior to Covid, was part of the launch of an online graduate program at her institution, so she had already spent some time thinking about and developing online courses. She also had previous online teaching experience from a previous position, but at her current institution, she said “I saw a lot of senior faculty”– and she was careful in explaining she meant faculty at her new institution who weren’t necessarily a lot older but who had not taught online previously– “try to take the classroom and put it online, and that doesn’t work. Because online is a different medium and it requires different teaching practices and approaches.” She went on to explain that her current institution sees itself as a “residential university” and the online graduate courses were “targeted towards veterans, working adults, that kind of thing.”

I think what this interviewee was implying is it did not occur to her colleagues who decided to teach synchronously to do it any other way. As a different interviewee put it, inserting a lot of pauses along the way during our discussion, “I opted for the synchronous, just because… I thought it would be more… I don’t know, better suited to my own comfort levels, I suppose.” Though to be fair, this interviewee had previously taught online asynchronously (albeit some time ago), and he said “what I anticipated– wrongly I’ll add– that what doing it synchronously would allow me to do is set boundaries on it.” This is certainly a problem since teaching asynchronously can easily expand such that it feels like you’re teaching 24/7. There are ways to address those problems, but that’s a different presentation.

Now, a lot of my interviewees altered their teaching modes as the online experience went on. Many– I might even go so far as saying the majority– of those who started out teaching 100% synchronously with Zoom and holding these classes for the same amount of time as they would a f2f version of the same class did make adjustments. A lot of my interviewees, particularly those who teach things like first year writing, shifted activities like peer review into asynchronous modes; others described the adjustments they made to being like a “flipped classroom” where the synchronous time was devoted to specific student questions and problems with the assigned work and the other materials (videos of lectures, readings, and so forth) were all shifted to asynchronous delivery. And for at least one interviewee, the experience of teaching synchronously drove her to all asynch:

“So, my first go around with online teaching was really what we call here remote teaching. It’s what everybody was kind of forced into, and I chose to do synchronous, I guess, because I didn’t, I hadn’t really thought about the differences. I did that for one quarter. And I realized, this is terrible. I, I don’t like this, but I can see the potential for a really awesome online course, so now I only teach asynchronous and I love it.”

The third reason for the choice between synchronous versus asynchronous is what I’d describe as “for the students,” though what that meant depends entirely on the type of students the interviewee was already working with. For example, here’s a quote from a faculty member who taught a large lecture class in communications at a regional university that puts a high priority on the residential experience for undergraduates:

The third reason for the choice between synchronous versus asynchronous is what I’d describe as “for the students,” though what that meant depends entirely on the type of students the interviewee was already working with. For example, here’s a quote from a faculty member who taught a large lecture class in communications at a regional university that puts a high priority on the residential experience for undergraduates:

“A lot of our students were asking for the synchronous class. I mean… when I look back at my student feedback, people that I literally wouldn’t know if they walked in the room because all I had (from them) was a black (Zoom) screen with their name on it, (these students said) ‘really enjoyed your enthusiasm, it made it easy to get out of bed every morning,’ you know, those kind of things. So I think they were wanting punctuation to just not an endless sea of due dates, but an actual event to go to.”

Of course, the faculty who had already been teaching online and were teaching asynchronously said something similar: that is, they explained that one of the reasons why they kept teaching asynchronously was because they had students all over the world and it was not possible to find a time where everyone could meet synchronously, that the students were working adults who needed the flexibility of the asynchronous format, and so forth. I did have an interviewee– one who was experienced at teaching online asynchronously– comment on the challenge students had in adjusting to what was for them a new format:

“What I found the following semester (that is, fall 2020 and after the emergency remote teaching of spring 2020) was I was getting a lot of students in my class who probably wouldn’t have picked online, or chosen it as a way of learning. This has continued. I’ve found that the students I’m getting now are not as comfortable online as the students I was getting before Covid…. It’s not that they’re not comfortable with technology…. But they’re not comfortable interacting in an online way, maybe especially in an asynchronous way… so I had some struggles with that last year that were really weird. I had the best class I’ve had online, probably ever. And the other (section) was absolutely the worst, but I run them with the same assignments and stuff.”

Let me turn to the second question I wanted to discuss here: “Knowing what you know now and after your experience teaching online during the 2020-21 school year, would you teach online again– voluntarily– and would you prefer to do it synchronously or asynchronously?” It’s an interesting example of how the raw survey results become more nuanced as a result of both parsing those results a bit and conducting these interviews. Taken as a whole, about 58% of all respondents agreed or strongly agreed with the statement “In the future and after the pandemic, I am interested in continuing to teach at least some of my courses online.” My sense– and it is mostly just a sense– that prior to Covid, a much smaller percentage of faculty would have any interest in online teaching. But clearly, Covid has changed some minds. As one interviewee said about talking to faculty new to online teaching at her institution:

Let me turn to the second question I wanted to discuss here: “Knowing what you know now and after your experience teaching online during the 2020-21 school year, would you teach online again– voluntarily– and would you prefer to do it synchronously or asynchronously?” It’s an interesting example of how the raw survey results become more nuanced as a result of both parsing those results a bit and conducting these interviews. Taken as a whole, about 58% of all respondents agreed or strongly agreed with the statement “In the future and after the pandemic, I am interested in continuing to teach at least some of my courses online.” My sense– and it is mostly just a sense– that prior to Covid, a much smaller percentage of faculty would have any interest in online teaching. But clearly, Covid has changed some minds. As one interviewee said about talking to faculty new to online teaching at her institution:

“A lot of them said, ‘you know, this isn’t as onerous as I thought, this isn’t as challenging as I thought.’ There is one faculty member who started teaching college in 1975, so she’s been around for a while. And she picked it up and she’s like ‘You know, it took a little time to get used to everything, but I like it. I can do the same things, I can reach students and feel comfortable.’ And in some ways, that’s good because it will prolong some people’s careers. And in some ways, it’s not good because it will prolong some people’s careers. It’s a double-edged sword, right?”

My interviewee who I quoted earlier about making the switch from synchronous to asynchronous was certainly sold. She said that she was nearing a point in her career “where I thought I’m just gonna quit teaching and find another job, I don’t know, go back to trade school and become a plumber.” Now, she is an enthusiastic advocate of online courses at her institution, describing herself as a “convert.”

“I use that word intentionally. I gave a presentation to some graduate students in our teacher training class, I was invited as a guest speaker, and I had big emoji that said ‘hallelujah’ and there were doves, and I’m like this is literally me with online teaching. The scales have fallen from my eyes, I am reborn. I mean, I was raised Catholic so I’m probably relying too much on these religious metaphors, but that’s how it feels. It really feels like a rebirth as an instructor.”

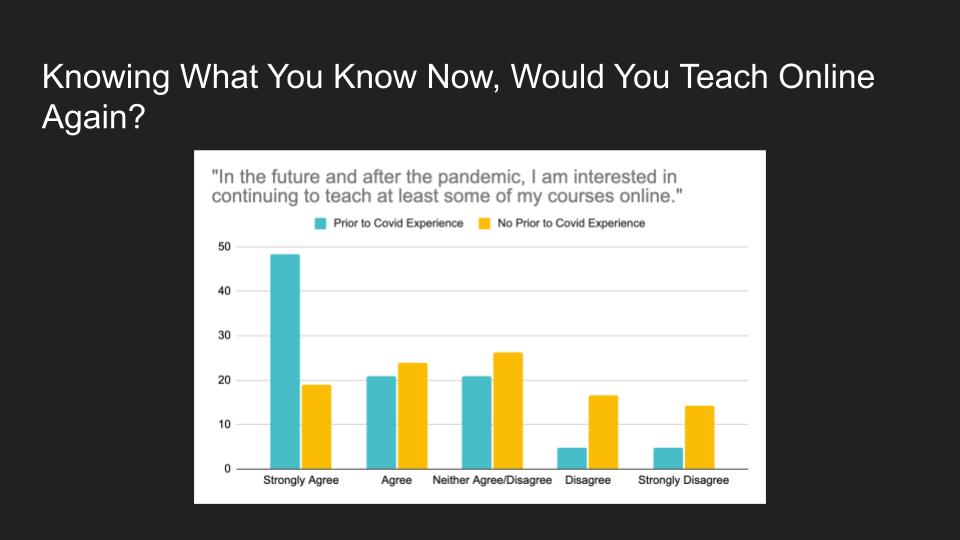

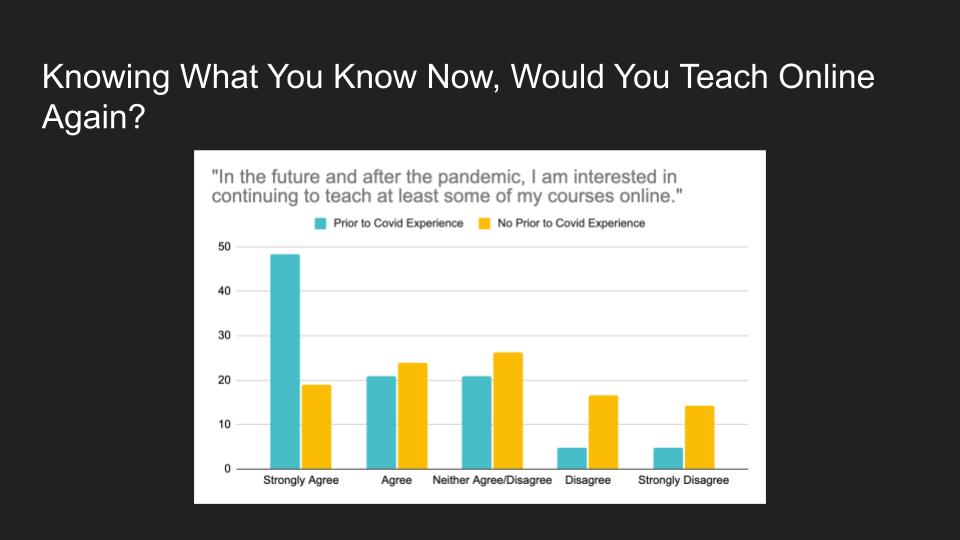

Needless to say, not everyone is quite that enthusiastic about the prospect of teaching online again. This chart, which is part of the article I’m writing for Computers and Composition Online, indicates the different answers to this question based on previous experience. While almost 70% of faculty who had online teaching experience prior to Covid strongly agreed or agreed about teaching online again and after the pandemic, only about 40% of faculty with no online teaching experience prior to Covid felt the same way. If anything, I think this chart indicates mostly ambivalent feelings among folks new to online teaching during covid about teaching online again: while more positive than negative, it’s worth noting that most faculty who had no prior online teaching experience neither agreed nor disagreed about wanting to teach online in the future.

Needless to say, not everyone is quite that enthusiastic about the prospect of teaching online again. This chart, which is part of the article I’m writing for Computers and Composition Online, indicates the different answers to this question based on previous experience. While almost 70% of faculty who had online teaching experience prior to Covid strongly agreed or agreed about teaching online again and after the pandemic, only about 40% of faculty with no online teaching experience prior to Covid felt the same way. If anything, I think this chart indicates mostly ambivalent feelings among folks new to online teaching during covid about teaching online again: while more positive than negative, it’s worth noting that most faculty who had no prior online teaching experience neither agreed nor disagreed about wanting to teach online in the future.

For example, here are a couple of responses that I think suggest that ambivalence:

For example, here are a couple of responses that I think suggest that ambivalence:

“Um, I would do it again… even though I would imagine a lot of students would say they didn’t have very positive experiences for all different kinds of reasons over the last two years, but now that we have integrated this kind of experience into our lives in a way that, you know, will evolve, but I don’t think it will go away…. I’d have to be motivated (to teach online again), you know, more than just do it for the heck of it. Like if I could just as well teach the class on campus, I still feel like face to face in person conversation is a better modality. I mean, maybe it will evolve and we’ll learn how to do this better.”

And this response:

“The synchronous teaching online is far more exhausting than in person synchronous teaching, and… I don’t think we cover as much material. So my tendency is to say for my current classes, I would be hesitant to teach them online at my institution, because of a whole bunch of different factors. So I would tend to be in the probably not category, if the pandemic was gone. If the pandemic is ongoing, then no, please let’s stay online.”

And finally this passage, which is also closer to where I personally am with a lot of this:

“If people know what they’re getting into, and their expectations are met, then asynchronous or synchronous online instruction, whether delivery or dialogic, it can work, so long as there is a set of shared expectations. And I think that was the hardest thing about the transition: people who did not want to do distance education on both sides, students and instructors.”

That issue of expectations is critical, and I don’t think it’s a point that a lot of people thought a lot about during the shift online. Again, this research is ongoing, and I feel like I am still in the note-taking/evidence-gathering phase, but I am beginning to think that this issue of expectations is really what’s critical here.

Ten or so years ago, when I would have discussions with colleagues skeptical about teaching online, the main barrier or learning curve issue for most seemed to be the technology itself. Nowadays, that no longer seems to be the problem for most. At my institution (and I think this is common at other colleges as well), almost all instructors now use the Learning Management System (for us, that’s Canvas) to manage the bureaucracy of assignments, grades, tests, collecting and distributing student work, and so forth. We all use the institution’s websites to handle turning in grades for our students and checking on employment things like benefits and paychecks. And of course we also all use the library’s websites and databases, not to mention Google. I wouldn’t want to suggest there is no technological learning curve at all, but that doesn’t seem to me to be the main problem faculty have had with teaching online during the 2020-21 school year.

Rather, I think the challenges have been more conceptual than that. I think a lot of faculty have a difficult time understanding how it is possible to teach a class where students aren’t all paying attention to them, the teacher, at the same time and instead they are participating in the class at different times and in different places, and not really paying attention to the teacher much at all. I think a lot of faculty– especially those new to online teaching– define the act of teaching as standing in front of a classroom and leading students through some activity or by lecturing to them, and of course, this is not how asynchronous courses work at all. So I would agree that the expectations of both students and teachers needs to better align with the mode of delivery for online courses to work, particularly asynchronous ones.

The other issue though is in the assumption about the kind of students we have at different institutions. When I first started this project, the idea of teaching an online class synchronously seemed crazy to me– and I still think asynchronous delivery does a better job of taking advantage of the affordances of the mode– but that was also because of the students I have been working with. Faculty who were used to working almost exclusively with traditional college students tended to put a high emphasis on replicating as best as possible the f2f college experience of classes scheduled and held at a specific time (and many did this at the urging of their institutions and of their students). Faculty like me who have been teaching online classes designed for nontraditional students for several years before Covid were actively trying to avoid replicating the f2f experience of synchronous classes. Those rigidly scheduled and synchronous courses are one of the barriers most of the students in my online courses are trying to circumvent so they could finish their college degrees while also working to support themselves and often a family. In effect, I think Covid revealed more of a difference between the needs and practices of these different types of students and how we as faculty try to reach them. Synchronous courses delivered via Zoom to traditional students were simply not the same kind of online course experience as the asynchronous courses delivered to nontraditional students.

Well, this has gone on for long enough, and if you actually got to this last slide after reading through all that came before, I thank you. Just to sum up and repeat my “too long, didn’t read” slide:

Well, this has gone on for long enough, and if you actually got to this last slide after reading through all that came before, I thank you. Just to sum up and repeat my “too long, didn’t read” slide:

I think the claims I make here about why faculty decided to teach synchronously or asynchronously during Covid are going to turn out to be consistent with some of the larger surveys and studies about the remarkable (in both terrible and good ways) 2020-21 school year now appearing in the scholarship. I think the experience most faculty had teaching online convinced many (but not all) of the skeptics that an online course can work as well as a f2f course– but only if the course is designed for the format and only if students and faculty understand the expectations and how the mode of an online class is different from a f2f class. In a sense, I think the “natural experiment” of online teaching during Covid suggests that there is some undeniable self-selection bias in terms of measuring the effectiveness of online delivery compared to f2f delivery. What remains to be seen is how significant that self-selection bias is. Is the bias so significant that online courses for those who do not prefer the mode are demonstrably worse than a similar f2f course experience? Or is the bias more along the lines to my own “bias” against taking or teaching a class at 8 am, or a class that meets on a Friday? I don’t know, but I suspect there will be more research emerging out of this time that attempts to dig into that.

Finally, I think what was the previous point of resistance for teaching online– the complexities of the technology– have largely disappeared as the tools have become easier to use and also as faculty and students have become more familiar with those tools in their traditional face to face courses. As a result of that, I suspect that we will continue to see more of a melding of synchronous and asynchronous tools in all courses, be they traditional and on-campus courses or non-traditional and distance education courses.